December 13, 2025

What is a system of equations?

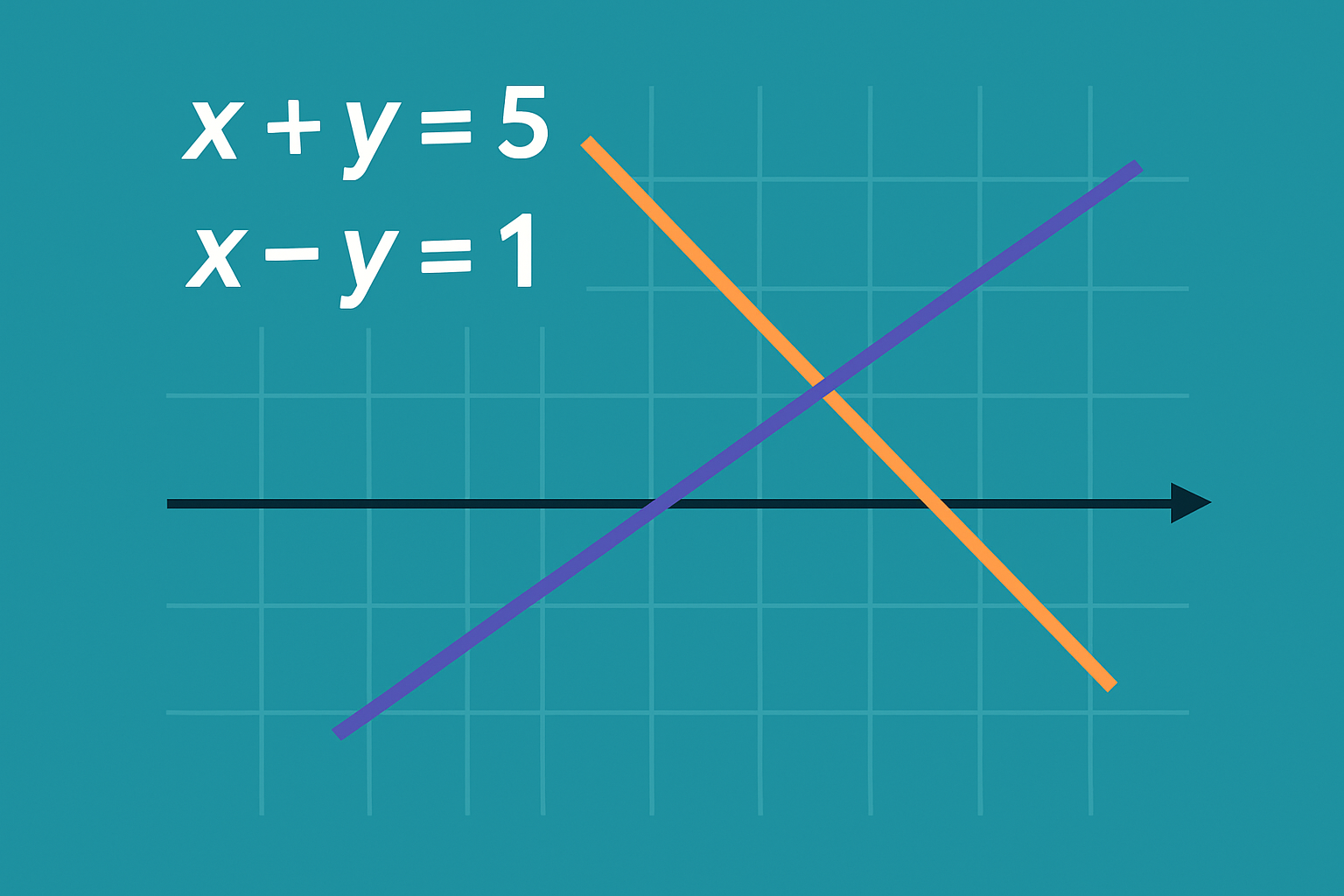

A system of equations is a set of two or more equations that must be true at the same time, usually involving the same variables. Each equation is a condition, but the system asks for values that satisfy all conditions together. For two-variable linear systems, you can picture each equation as a line on a graph, and the solution is where the lines intersect. Depending on how the equations relate, a system can have one solution (lines cross once), no solution (lines are parallel), or infinitely many solutions (the equations describe the same line). Systems of equations matter because real problems rarely have just one constraint, and they show up in business, engineering, science, and computing whenever you need a single set of values that fits multiple rules.

A single equation is one rule that links unknowns (variables) together. A system of equations is simply two or more equations that must be true at the same time, usually involving the same variables. The point of a system is to find values of the variables that satisfy every equation in the set, not just one of them.

A single equation is one rule that links unknowns (variables) together. A system of equations is simply two or more equations that must be true at the same time, usually involving the same variables. The point of a system is to find values of the variables that satisfy every equation in the set, not just one of them.

If one equation is a single “constraint,” then a system is a set of constraints that all apply simultaneously. In real problems, that’s common: you rarely have only one condition. You might have a budget limit and a time limit. Or two measurements describing the same object. Or supply and demand rules that must both hold.

A simple example

Consider these two equations:

- (x + y = 10)

- (x - y = 2)

Each equation alone has infinitely many solutions. For example, (x + y = 10) is true for ((x,y) = (0,10), (1,9), (2,8)), and so on. But the system asks: which pair works for both equations? If you add the equations, you get:

(x+y)+(x−y)=10+2⇒2x=12⇒x=6

Substitute back into (x + y = 10): (6 + y = 10 \Rightarrow y = 4).

So the system’s solution is ((x, y) = (6, 4)).

That’s what “solving a system” means: finding the intersection of conditions.

How to think about systems visually

Systems become much clearer when you connect them to geometry.

Two variables: lines meeting in a plane

When a system has two variables (like (x) and (y)) and both equations are linear (straight-line equations), each equation represents a line on the coordinate plane. Solving the system means finding the point where the lines intersect.

There are three main possibilities:

- One solution: the lines intersect at exactly one point.

- No solution: the lines are parallel and never meet (inconsistent system).

- Infinitely many solutions: the lines are actually the same line (dependent system).

Example of no solution:

- (x + y = 5)

- (x + y = 9)

These can’t both be true for the same ((x,y)), so the system is inconsistent.

Example of infinitely many solutions:

- (2x + 2y = 10)

- (x + y = 5)

The first equation is just the second multiplied by 2, so they describe the same line.

Three variables: planes meeting in space

With three variables ((x, y, z)), each linear equation represents a plane in 3D space. A system might have one solution (planes intersect at a single point), no solution (planes don’t share a common point), or infinitely many solutions (planes intersect along a line or coincide).

What counts as a “solution”?

A solution to a system is any set of values for the variables that makes every equation true. The variables can be numbers, but in higher math they can also be functions, vectors, or other objects. In basic algebra, you’re usually solving for numbers.

Also, a system can be:

- Linear: variables are only to the first power, not multiplied together (e.g., (3x - 2y = 7)).

- Nonlinear: includes squares, products like (xy), roots, trig, etc. (e.g., (x^2 + y^2 = 25)).

Nonlinear systems often produce multiple solutions, or solutions with more complex shapes than straight lines.

Common methods to solve systems

For two-variable linear systems, three methods are standard:

- Substitution

Solve one equation for one variable, then substitute into the other equation. - Elimination (addition/subtraction)

Add or subtract equations to eliminate a variable, like in the earlier example. - Graphing

Draw both equations and read the intersection point(s). This is intuitive but not always precise unless the intersection is clean.

For bigger systems (many equations and variables), you usually switch to matrix methods like Gaussian elimination. That’s the same elimination idea, just organized efficiently.

Why systems of equations matter

Systems are everywhere because most real situations involve multiple conditions at once. Examples:

- Business: pricing, profit constraints, inventory limits.

- Engineering: forces and equilibrium in structures.

- Computer science: modeling networks, optimizing resources, solving constraints.

- Science: chemical reactions, population models, electrical circuits (Kirchhoff’s laws).

Whenever you need a set of values that satisfies multiple rules simultaneously, you’re in “system of equations” territory.

The core idea

A system of equations is not “hard math” by definition. It’s just multiple truths that must hold at the same time. Solving it means finding the shared solution set. Sometimes that set is one point, sometimes none, sometimes infinitely many. Once you understand that you’re looking for the overlap, the rest is technique.

You can use our calculator: https://globalcalcbox.cloud/math/system-equations